A world of ‘lush longing for embroidered handkerchiefs and soft kisses’ is interrupted by a police campaign to achieve the downfall of the cross-dressing pair.

A world of ‘lush longing for embroidered handkerchiefs and soft kisses’ is interrupted by a police campaign to achieve the downfall of the cross-dressing pair.

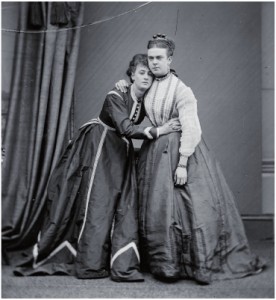

In 1870, two tatty-looking girls were hauled before Bow Street magistrates court and charged with “the abominable crime of buggery”. After a night in the cells, with wigs slipping and stubble poking through, it was pretty clear to the packed and panting courtroom that the two tarts were actually young men. Their names, according to the charge sheet, were Ernest Boulton and Frederick Park. To their friends they were Stella and Fanny. And in the newspapers, where they now became front-page fixtures, they were known as the He-She Ladies.

There had been men dragging up and selling sex for decades on the streets of London without the authorities paying quite such savage attention. But, in 1870, Britain had the jitters. At home, the Republican movement was reaching tipping point, Darwin’s monkey talk had turned men into beasts, while just across the water Paris had become a commune. It was a topsy-turvy kind of world and the sight of two young men in frocks only added to the disturbing sense that things were out of joint. One way of restoring order might be to put the sexes back in their proper places. Hence Boulton and Park’s sensational appearance in court: significantly, and spitefully, they had not been allowed to change into men’s clothing before climbing into the dock.

The previous evening the young men had been out on a particularly audacious “spree”, camping it up in a private box at the Strand theatre and, most shocking of all, using the ladies’ lavatories. Stella and Fanny’s outlandish appearance and mincing manners, though, were the least of their crimes. “Personating a woman” in public was merely a “misdemeanor” and might be dealt with by a fine and a good talking-to. What mattered, from the court’s point of view, was whether penis and anus had ever met.

And that, of course, was hard to say. While Stella and Fanny might be the most terrible show-offs, not to mention industrious sex workers, even they drew the line at coupling in public places. Over the course of the subsequent trial, and despite bribing witnesses, the prosecution failed to prove that sodomy had ever occurred, either between the two young men themselves, or within their circle of genteel “sisters”, or even in a dark corner behind the Haymarket with a passing guardsman. Eventually, and only after a second trial a year later, the young men were found not guilty and allowed to slip back into their lives of pro-am theatricals, touring together and separately in such limp pieces as A Comical Countess and A Morning Call.

Neil McKenna uses the meticulous court records from the two trials, together with the associated evidence – letters, mainly, between the accused and their confederates – to reconstruct the story of how Boulton and Park got to be Stella and Fanny. Both were born into solidly middle-class homes, the son of a stockbroker and judge respectively. Both were fey, precocious boys who failed to buckle down to the dull clerking jobs found for them by worried parents. Both had drifted towards those particular stretches of the London streets where men paid for sex with women who might be men, or with men who looked like women or, after a night of heavy drinking, with anyone who might be anything at all. Kept on short financial rations at home, Stella, the pretty one, and Fanny, less favoured but kind-hearted, needed the extra cash for all those silk stockings.

What makes this book such a startling read is the way that McKenna recreates the affective world of Stella, Fanny and their “sisters”, a loose cohort of half a dozen young gay men, some of whom stood trial. Extrapolating from their letters, McKenna plunges us into a world of lush longing for embroidered handkerchiefs, soft kisses and husbands with titles (at one point Stella even has a card printed up announcing herself as Lady Arthur Clinton). This is a world of butterfly glamour perched unsteadily atop a real one of permanent pissedness, grubby stockings and painful anal sores.

“Extrapolate” is the key word here, though. For letters, no matter how intimate and fine-grained, rarely tell the biographer the thing he longs to know: the moment his subject sighed, or felt a lurch in his guts, or longed to be somewhere else entirely. And, although McKenna scrupulously uses the sources when he’s got them, at those points where the archive runs out he allows his imagination to take over. Using free indirect speech he ventriloquises Stella and Fanny’s inner worlds, creating a camp stream of consciousness in which the two young men think and function as lascivious women.

He does the same thing, quite brilliantly too, with Boulton’s mother, whose Christian name, Mary Ann, was ironically the slang name for a male prostitute. Rummaging in Mrs Boulton’s muddled mind, McKenna creates a wonderful sense of how a fond and foolish mother might simultaneously know and not know what her son was up to. Mary Ann lent young Ernie her dresses, fussed over his friends and found their habit of using girls’ names simply charming.

And she exploded with pride when Lord Arthur Clinton became Ernie’s special friend. Her genuine naivety on the witness stand went a long way towards getting the two young men released. That, and the fact that their prosecution was clearly a put-up job. If the English hated anything more than sodomy, it was a police force acting beyond its proper powers.

Boulton and Park have long been one of the star turns of deviant Victorian sexuality, along with Arthur Munby and James Miranda Barry. McKenna does an excellent job of dusting them down for the 21st century, testing the limits of his documentary source material and showing what happens when the biographer allows himself the licence to go inside his subject’s head.

His writing has much of the performative element that characterised Stella and Fanny’s appearances on the streets of London and in provincial halls. Showy as a feather boa, McKenna’s text takes pleasure in its own silly excess. There are drawers galore, plenty of back passages and chapter titles such as Monstrous Erections, which turns out to refer to the size of his heroines’ wigs.

Purists and puritans may balk at the book, both its tone and its way of proceeding. But everyone else will have a ball.